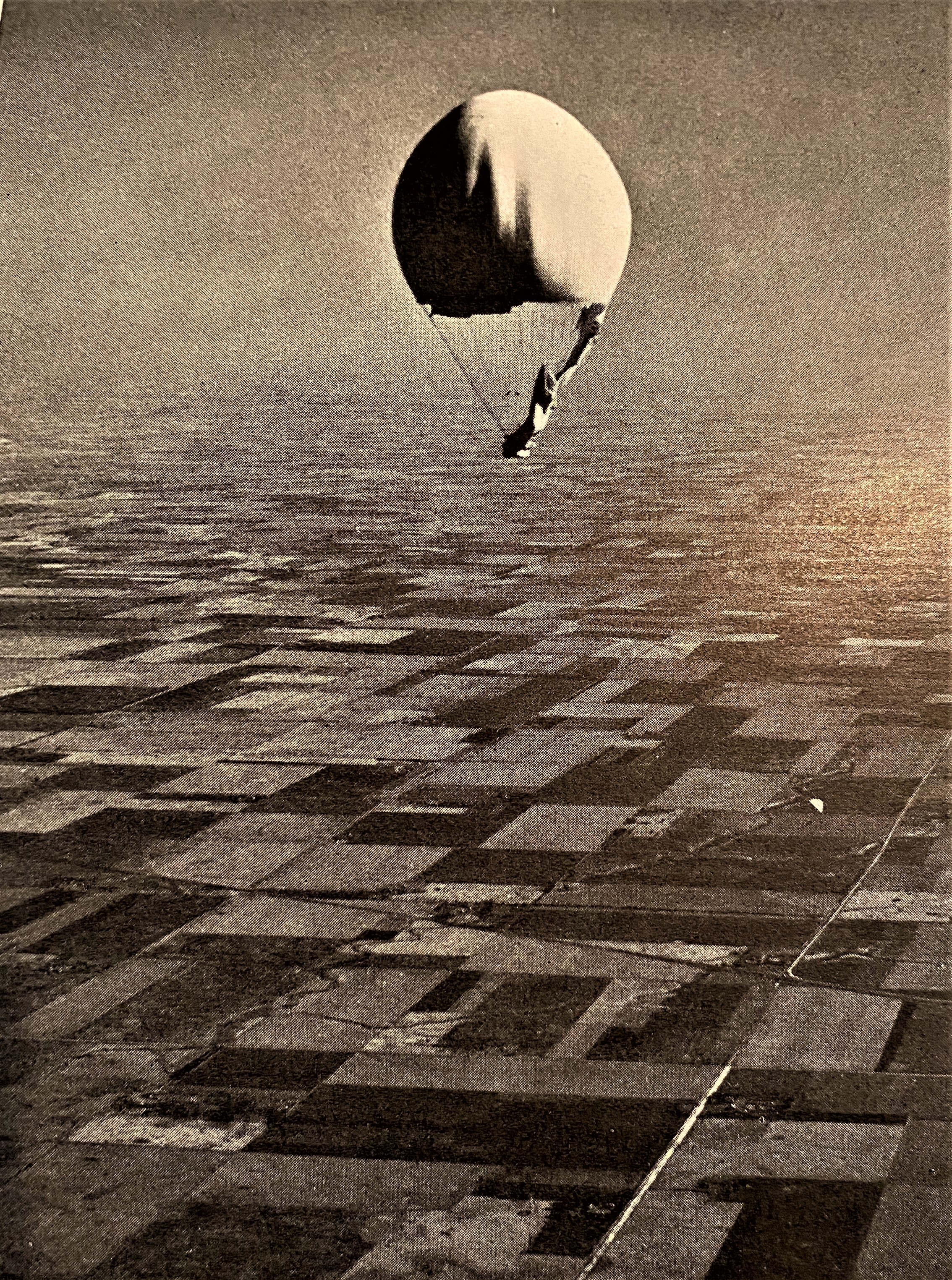

Image Courtesy of National Geographic, October 1934

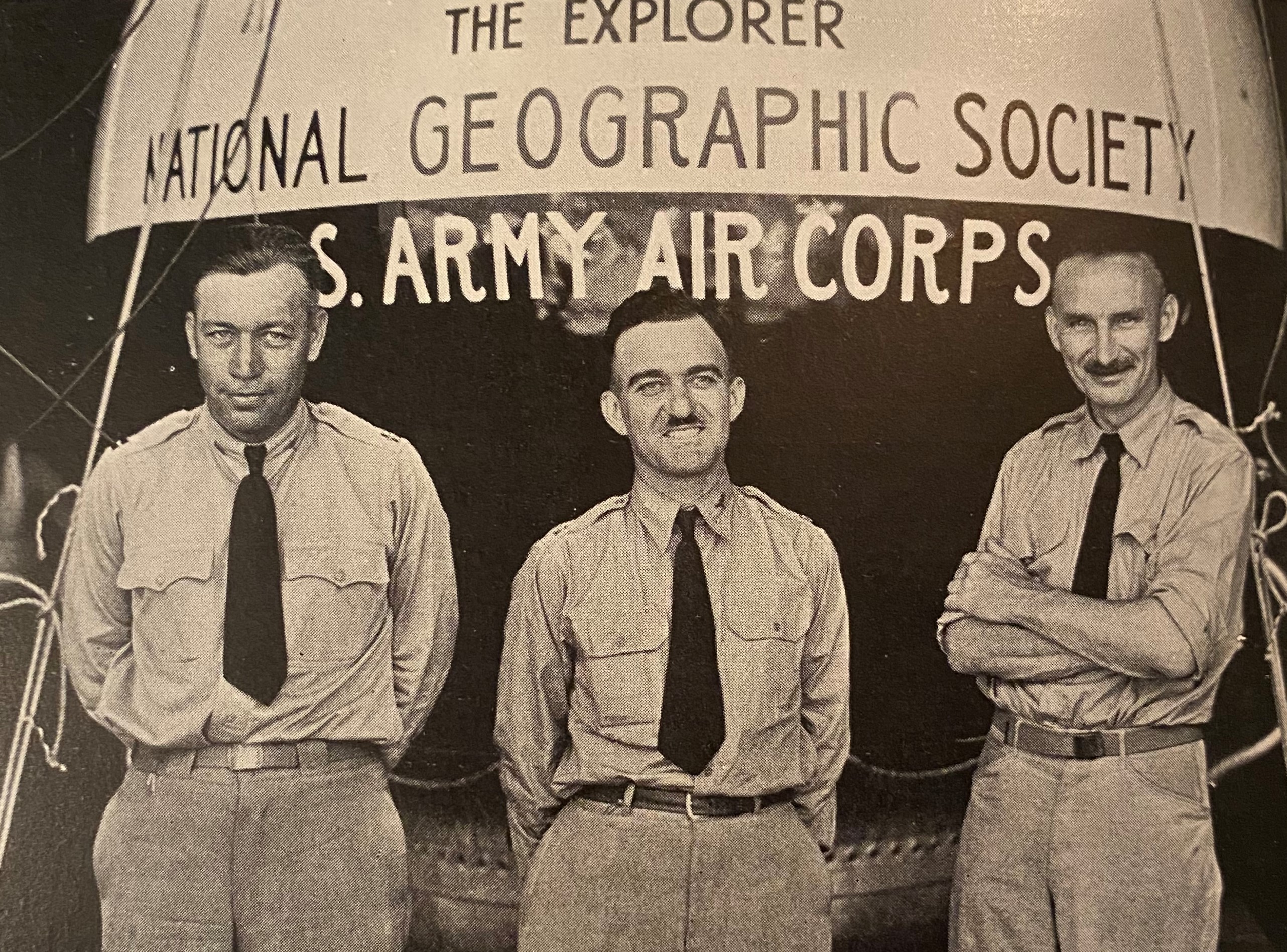

Explorer I was the first of the four balloon flights out of the Stratobowl and was founded by the United States Army Corps and the National Geographic Society. It launched at 5:45 A.M. Mountain Standard Time on July 28th, 1934. The three pilots were Major William E. Kepner, Captain Albert Stevens, and First Lieutenant Orvil A. Anderson.

Explorer I's envelope was made by the Goodyear-Zeppelin Company and was filled with hydrogen gas expanded to 3,000,000 cubic feet in volume which lifted the 700 pound, 100 inch diameter gondola.

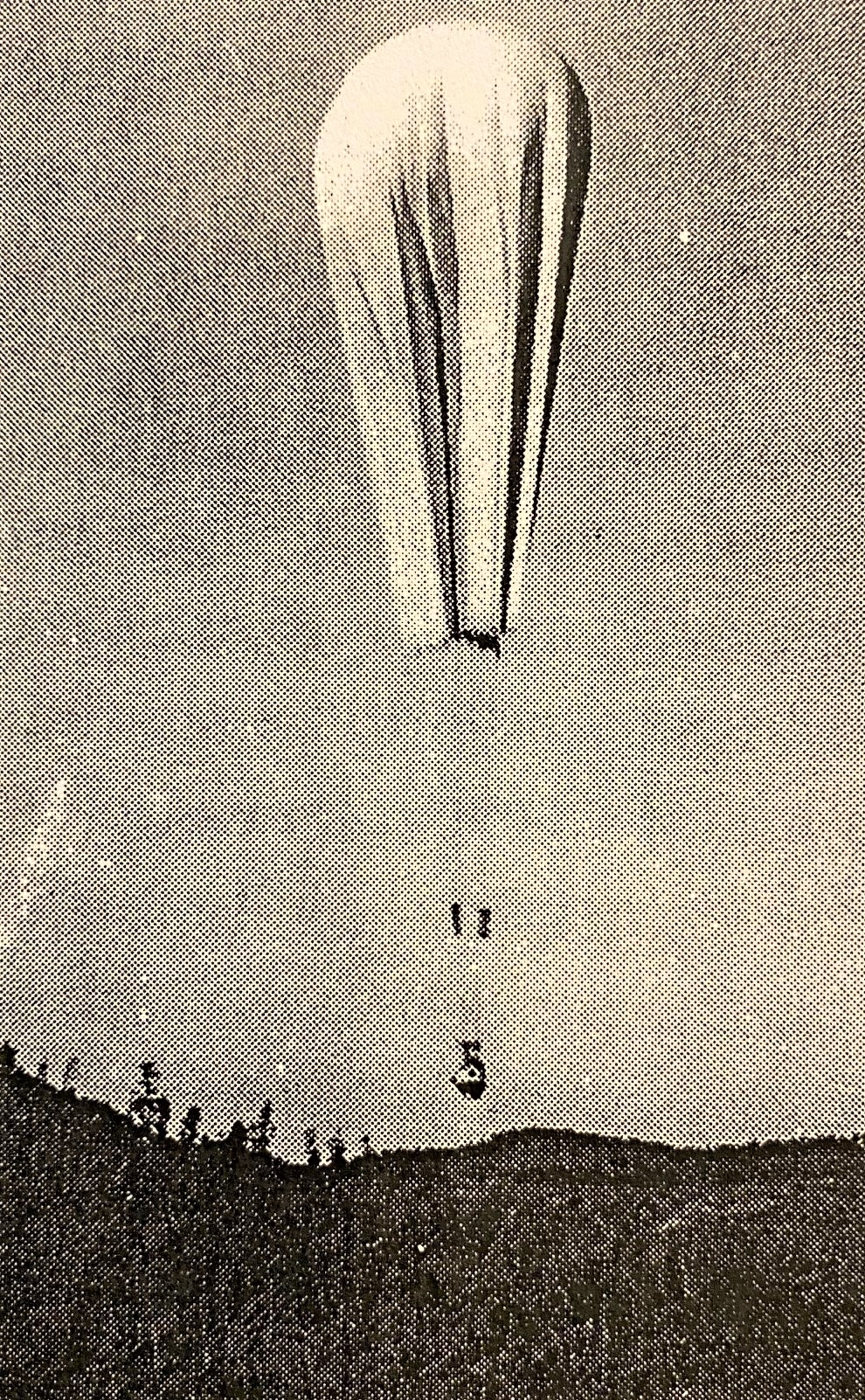

"On July 27th, the weather appeared right for a flight on the next day. A little past dusk the ground crew began inflating the balloon. By two o'clock in the morning the inflation was complete. At that time the envelope held 210,000 cubic feet of highly flammable hydrogen gas. As the Explorer ascended, the gas would expand and fully inflate the 3,000,000 cubic foot envelope at 65,000 feet. It was estimated that 50,000 spectators had gathered to watch the historic event. Kepner, Anderson, and Stevens climbed aboard the gondola and at 5:45 A.M. Kepner gave the command, "Cast off!" and the mighty balloon took off." Balloons Aloft: Flying South Dakota Skies

Image Courtesy of Miller Studio

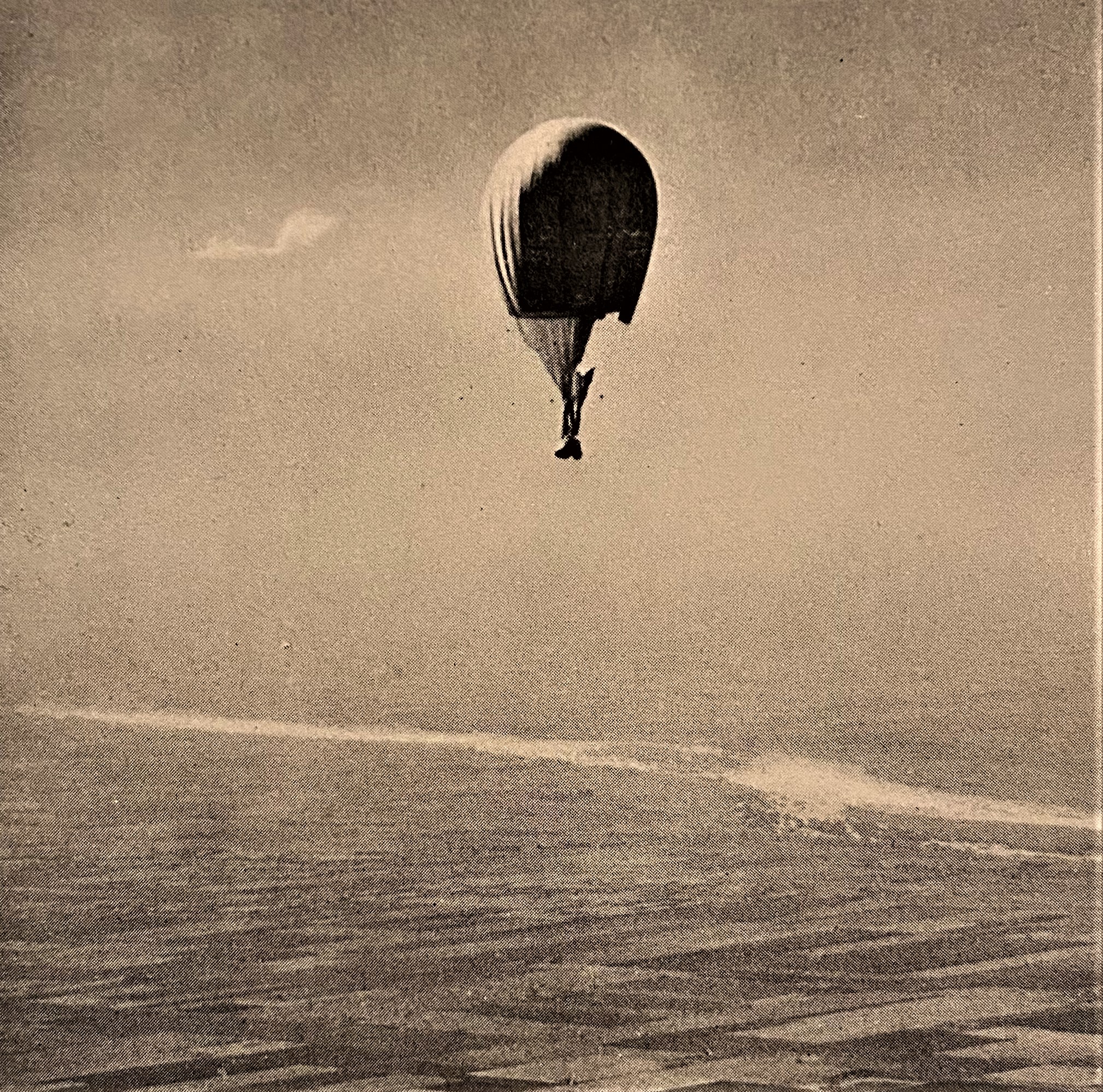

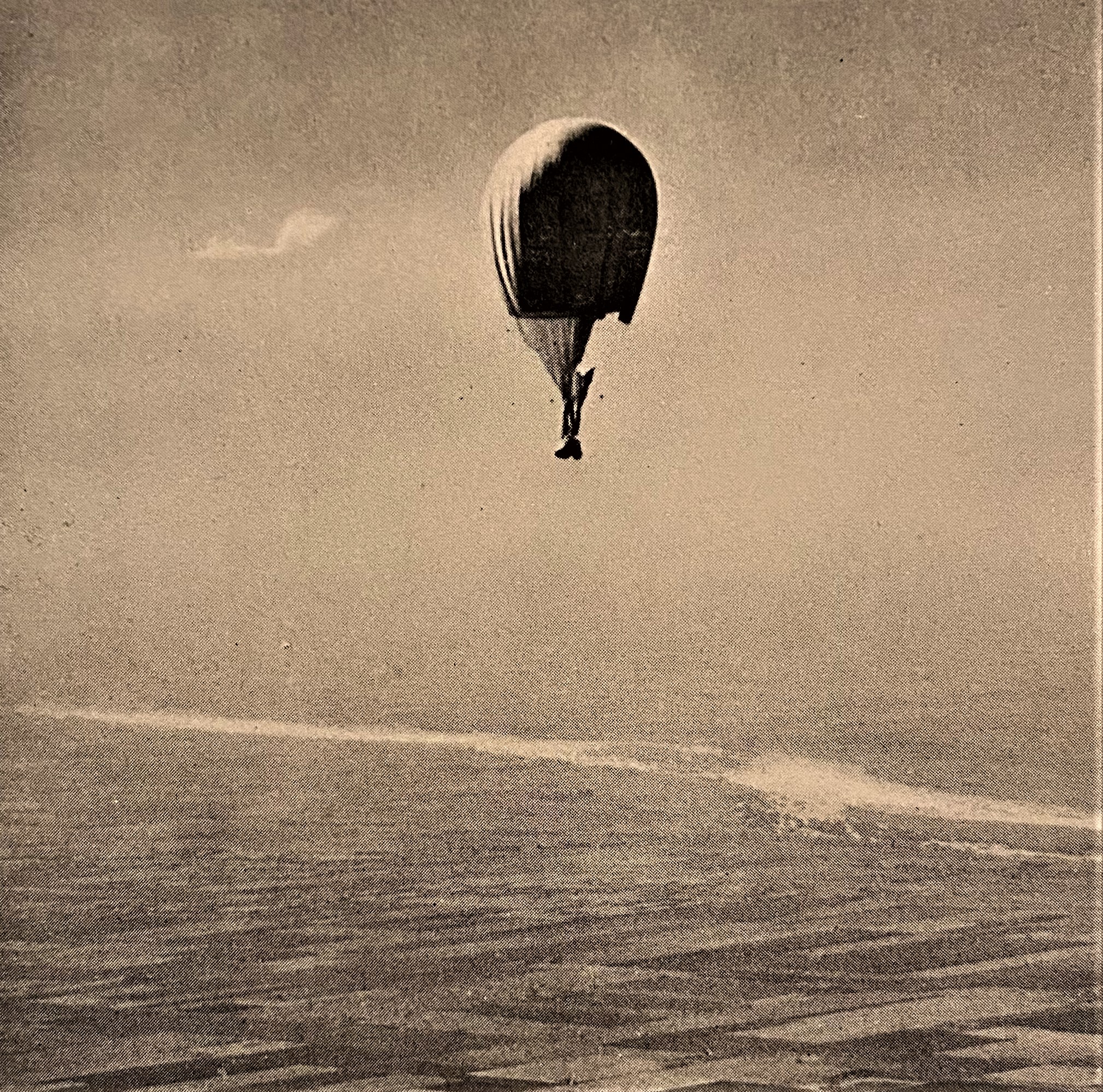

Images Courtesy of National Geographic, October 1934

Image Courtesy of Miller Studio

The three aeronauts would collect air samples, photograph the curvature of the earth, measure the intensity of cosmic rays, and gather data regarding the ozone layer. Soon the balloon reached 60,000 feet above sea level. Prior to this moment, only eight aeronauts in the world had ever been higher, and of those eight, only five survived to land. Just then a clattering noise and a thud was heard on top of the gondola. This concerned the aeronauts so they investigated. They discovered that part of the appendix cord, a small rope, fell on the roof of the gondola. There also appeared to be a rip in the bag. Stevens recalled, "Imagine our feelings for a few minutes. It looked as though the valve hose had parted along with the torn fabric. Had this happened we would have been helpless... through the overhead glass porthole we watched the rent in the fabric gradually become larger and larger. The minutes passed slowly by; the magnets of the cosmic ray instruments clattered on; the buzzers hammered on the barometer box; the instrument cameras clicked in unison at regular intervals... below us was the brown, sunbaked earth, so far away that no roads, railroads or houses could be made out. Our direction of drift was changing, but that was now a matter of little concern. The question now was not where we should get down, but how! Three quarters of an hour passed and we were down to 40,000 feet. Our speed was increasing and a half hour later we were down to 20,000 feet... when suddenly the entire bottom of the bag dropped out."

Image Courtesy of National Geographic, October 1934

Image Courtesy of National Geographic, October 1934

"Kepner and Anderson cut loose the spectrograph and it floated safely down to Earth on it's individual parachute. More ballast was discharged. With parachutes on, it was time to leave. Stevens writes, 'the altimeter reading it gave was 5,000 feet above sea level, we were in reality only a little more than half mile from the ground'."

Balloons Aloft: Flying South Dakota Skies

The aeronauts were clear to jump and Stevens went out first with Anderson second. Anderson's feet got stuck in the gondola and Kepner shouted, "Hey get your big feet out of the way, I want to jump." Kepner helped Anderson get out and they all made it safely to the ground. The gondola landed in Mr. Reuben Johnson's field near Holdrege, Nebraska.

"Major Kepner and I went to the farmhouse of Reuben Johnson, on whose field we had landed, to telephone and send some telegrams. For some time I had been conscious that it was nearly 100 degrees in the shade... and I still wore two suits of heavy woolen underwear and a light canvas flying suit; so in the farmhouse I asked permission to use a room to shed some clothing. In a few minutes I was dressed only in the canvas suit and I took the two suits of underwear outside and hung them over a fence. Then I went inside to get my messages off by telephone. When I came out, I found that souvenir hunters had taken my underwear!"

Captin Albert Stevens

The flight appeared to be a failure, since most of the instruments, including the electroscopes used to gauge cosmic rays, were smashed. The spectrograph was preserved by its own individual parachute. Luckily, about 163 out of 200 photos survived. Despite the loss, the flight of Explorer I was not a failure. It was a partial success and broke barriers by saving the spectrograph, photos, and achieving flight experience. National Geographic President, Grosvenor, had insured the flight with Lloyd's of London. The policy covered the balloon, gondola, and scientific instruments to the tune of $30,170.00. The U.S. Air Corps and the National Geographic Society began immediately to envision an Explorer II.

Video courtesy of Captain-Crystal Stout